27 Share Shokawa

a Masterclass project by Jek Kee Lim.

27 for the lot number,

shared amongst residents and locals of both old and young,

adaptively reusing Shiritsu Shokawa Junior High School.

In the heart of Japan, beneath the neon lights of Tokyo’s bustling streets and the serene beauty of cherry blossoms, lies a hidden world that seldom meets the eye. It’s a place shrouded in darkness, where social stigma weaves its sinister threads, and the shadows of abandonment loom large. This is the Japan that rarely makes it into tourist brochures or postcards, a place where abandoned schools echo with the ghosts of forgotten dreams, orphanages cradle lost souls, and lonely deaths unfold in the silence of aging apartments.

Beneath the veneer of prosperity and politeness, Japan grapples with a societal paradox. Orphans, or orphanages in Japan are not readily visible, for they are not only hidden in remote corners, but are also shrouded by a society that would rather pretend such issues do not exist. In Japan, the stigma surrounding single parenthood, adoption, and the very idea of abandoned children is a heavy cloak that conceals the truth. Volunteers that choose to help are shocked by the amount of work that is swamped by the staff, leaving the children unattended, resulting in children that are not even close to the academic level of their age. The gap with the world outside is enormous, as if time within the orphanage had stopped years ago. Japan’s declining birth rate and societal pressures only exacerbate this problem, and its ironic how orphans are not receiving sufficient education when schools around the country are closing down.

And then there are the elderly, Japan’s greying population, living out their twilight years in solitude. In the 1960s, the Japanese government built huge housing developments outside Tokyo and other cities, each holding thousands of young “salarymen” entrusted with rebuilding Japan’s post-war economy. The complexes — sprawling collections of buildings called 'danchi' — introduced Japan to a Western structure of life centred on the nuclear family, breaking from the traditional multi-generational homes. The elderly who have outlived their spouses, children, and friends, now face a lonely existence in cramped apartments. The rapid pace of modern Japanese society leaves many seniors behind, their days blending into one another, and their presence unnoticed by neighbours. Some meet their end in isolation, and their passing often goes unnoticed until a pungent odour fills the hallways, and authorities are called to investigate.

The essence of this project revolves around the idea of repurposing vacant schools to house widowed elders who originally hail from the area along with orphaned children. A project like this not only leverages the advantage of repurposing otherwise dormant buildings but also fosters a range of local cultural activities, including workshops that both residents and visitors can participate in. What was once a seemingly lifeless building can transform into a vibrant cultural hub, where people can gather, mingle, and allow residents of this project, who were once isolated from the world around them, to potentially reconnect with society.

One such vacant school can be found nestled in the mountainous regions of Shokawa, Takayama. The Shiritsu Shokawa Junior High School likely fell victim to vacancy, mirroring the fate of countless defunct schools strewn across Japan's countryside. The exodus of young people migrating to urban centers in search of better job prospects and a more dynamic lifestyle has led to a decline in the number of school-age children in rural communities. However, during my contextual studies, what piqued my interest about this location, aside from the concentration of amenities to the north and south, was the presence of a newly constructed hotel just 300 meters north of the site. Using it as a defining marker that symbolizes the influx of visitors, I have chosen this location as my site.

27 Share Shokawa features a residential extension, primarily made from timber that attaches itself to the vacant junior high school. Its design language was derived closely from the Katsura Imperial Villa, which was regarded by many, captures the essence of traditional Japanese architecture, reflected upon its heavy emphasis on revolving around nature. Looking closer into the axonometric section, one can find small human figures, people of various ages scattered across different corners of the project, sharing food and conversation. And looking at it from this perspective, well, what is it? Is it a farm? Is it a workshop? Or perhaps a dwelling? The answer is a cross between all of these. They are everything, and none.

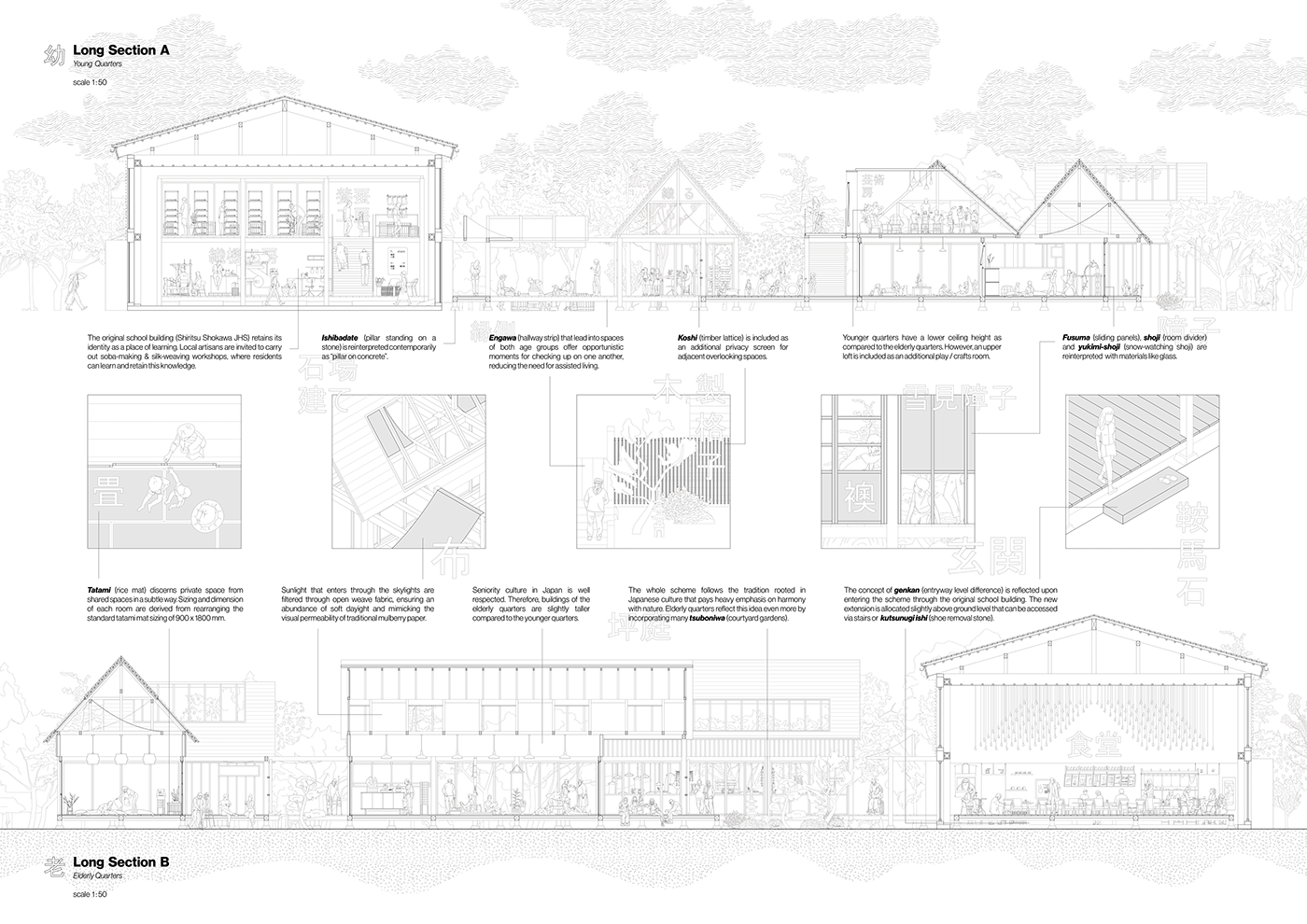

The complex can be divided into 4 distinct sections. First and foremost, we have the school, which incorporates silk-cultivation workshops and community kitchens for traditional soba-making. It also serves as the public entrance to the scheme. Local artisans can be invited to conduct workshops here, sharing their skills and knowledge not only with the residents but also with tourists and visitors. This presents a valuable opportunity, particularly for orphans, who can learn technical skills that would facilitate their reintegration into society. In the centre, a large clearing is dedicated to cultivating mulberry and buckwheat, while an outdoor gathering space provides an ideal venue for events and festivities. Residents can also volunteer and work at the cafeteria and market area, where they can sell produce and DIY crafted items.

On the left side, we find the elderly quarters, while on the right, the young quarters, and in the centre, the mixed quarters. Delicate design choices were made to distinguish one from the other. In the elderly quarters, 'tsuboniwa' (small pocket gardens), are more prominently featured. The buildings in this section also stand slightly taller, reflecting Japan's reverence for seniority. In the younger quarters, the buildings are arranged more closely together without pocket openings, and an upper level has been integrated for children to engage in arts and crafts. Lastly, the mixed quarters combine design elements from both sides, creating a harmonious blend of spaces.

When examining the sections, it becomes evident that the new intervention is positioned slightly above ground level. This design draws inspiration from the traditional Japanese concept of 'genkan', where entryways feature a level difference, signifying the transition from the outside world to one's home. In this case, this level difference serves to distinguish the new addition from the existing structure as one ascends a level. Traditional architectural elements have been reinterpreted throughout this project. For instance, 'ishibadate', which originally referred to pillars on stone, has been transformed into pillars on concrete. Similarly, the lattice patterns of the traditional timber lattice door, known as 'koshi', have been extracted and repurposed as privacy screens for the overlooking spaces, among other adaptations. My favourite one of all was the use of fabric as a light diffuser. In ancient times, the concept of 'shoji', translucent paper screens, was primarily employed to disperse natural light into the interior of homes. With this concept in mind, skylights and fabric were used as a modern reinterpretation, allowing soft daylight not only to enter through the glazed façade but also to descend from above, creating a serene and inviting ambiance within the interiors.

As we reflect on the rich tapestry of history and contemporary needs, we stand at the intersection of tradition and progress, poised to address the pressing issues of our time. Through thoughtful design, repurposing, and a commitment to fostering connections among generations, I aspire to create spaces where the echoes of the past harmonize with the hopes of the future. A small project like this might seem insignificant in the grand scheme of resolving a complex social issue like this, however, I believe that a journey of a thousand miles, begins with a single step.